David Salle: Musicality and Humour - Skarstedt Gallery

Skarstedt is currently holding an exhibition of a new body of work by painter David Salle

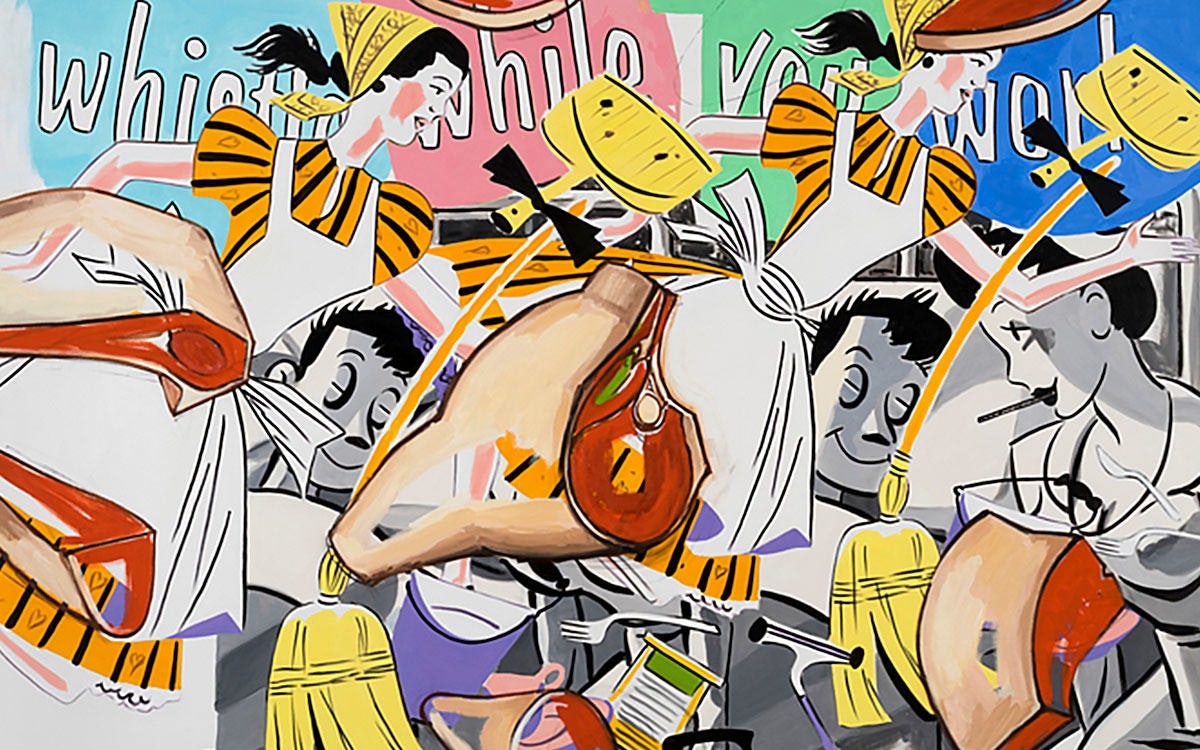

The arrangement of objects, sculpture, and images into immersive installation has become a constant for Anthea Hamilton, whose work frequently mines heterogeneous image sources. This includes The Prude, her Skarstedt is currently holding an exhibition of a new body of work by painter David Salle. Presented for the first time, these vibrant paintings showcase Salle’s continued preoccupation with composition - the process of establishing the relationships of everything in the painting to everything else - as both the engine of painting and its subject. All the elements of painting are relational, and their relations can either be fixed, or liable to shift. Salle has made the shifting, swirling, dynamic of pictorial/spatial relationships his arena. Un-equal, or un-stable relationships are one of the sources of humour in Salle’s work. Images and objects, as they are depicted in his paintings have a way of confounding assumptions; often one image will conjoin with another, or turn out to be something else entirely, according to the context. His paintings set out the conditions for and make use of these shifting relationships; their result is painting’s ‘narrative capital.’ That is, narrative is a result, and not the driving force of these pictures. Their subject is the way pictorial relationships can be organised around, and highlight certain principles or effects: humour, narrativity, dissonance, melancholy, or sentiment. The principle recurring element in the current series, are enlarged details of black and white renderings of drawings made in the 1940s and ‘50s. The subjects as well as their treatment are dated, from another era. For Salle, “to repaint them – is to make a kind of history painting. The paintings are not about the cartoons; they freely take from the world that the cartoonist concocted – out of what were already in their time, well-worn tropes of low comedy. Exaggeration. Cartoon slapstick. Of course, that’s just one element. The rest is free Jazz.” The other elements that run like musical passages through this series are predominantly from a similar period, a time when illustration was king. Cartoons and commercial imagery are in many ways shorthand, abbreviated examples of how representation works, how an image is broken down into light and shadow, and as such are useful for Salle to draw on in his interplay of colour and form. As with musical phrasing, Salle, working like both composer and conductor, shapes the sequence of forms in his paintings altering the tone, tempo and dynamics. “The paintings mix fast and slow tempos, their rhythms are syncopated, polyphonic. There is another musical analogy: the colour harmonies are like the intervals between notes that form a chord; precisely calibrated tones. Indeed, all of the elements that make up the paintings, the value patterns, as well as all the other relationships, of size and scale, of line to mass, of solid to open forms, loose to tight rendering, contrasting heavy and delicate lines, and especially the contrast between “repurposed” images and direct observation – all these elements and more express musical values.” The repetition of the cartoon, the bright t-shirts and the images of the housewife that dance across the canvas in Autumn Rhythm are like numerous consecutive phrases that make up the melody of the painting. Over this broomsticks and dustpans in bright yellow, which echoes the housewives’ head scarves, ring out like high notes. The cuts of meat are like beats throughout, at once solid sculptural forms and yet unfinished; they act as veils through which other forms can reassert themselves. The shapes and volumes of the meat – adapted by Salle from a diagram in a butcher’s manual – are also like architecture, monuments seen from the air, which themselves appear to be flying. In fact, many if not most, of the elements in these paintings are airborne, aloft, and every element, every mark and gesture within the painting contributes to an overall sense of rhythm and movement. Salle’s new body of paintings have rhythmic and imagistic complexity which we have come to expect, but they also have a high-keyed energy, intensity and visual clarity, an openness, that feels new and very much of this moment.irst exhibition at both London locations of Thomas Dane Gallery. For the prude, modesty becomes extreme. The prude will not permit themselves, or others, sensuous enjoyment in life. Hamilton's interest in the literary figure of "the prude" in part, references Cecil Vyse — the aloof character of E.M Forster's A Room with a View (1908). Perceiving himself a sensitive intellectual, Vyse in reality, remains detached from lived experience. This obstinate self-awareness is matched by a cultivated, exaggerated style. This skewed mode of being, the prude-as-persona, serves a framework for the exhibition, where the prude is put to use as a proxy for Hamilton, who performs a "hands off" physicality. The balance of materiality and economy is consistent with Hamilton's practice, where tactile surfaces are often conceived through digital production. Suggestive of previous exhibitions and series, The Prude is largely a continuation of Hamilton's The New Life at Secession, Vienna (2018). Four distinct interiors emphasise the confluence of domestic and gallery space through a number of wall treatments: airbrushed, textile clad and digitally printed wallpapers. One monochrome room at No.11 includes photographs by Lewis Ronald. Taken at Kettle’s Yard, the images show multidisciplinary artist Carlos Maria Romero interact with objects in the house, specifically, four brass rings and one jade ring (pre-1966) made by Richard Pousette-Dart. The Prude also challenges relationships of scale and content, with large soft sculptures of moths and butterflies, and extravagant stone, marble, and walnut wavy boots. The effect is less an analysis of artifice, more a consideration of the way objects and images may influence meaning when treated to different processes of realisation. Though Hamilton's use of material may appear mercurial, her approach to form remains acute. Hamilton's interest in the reducibility and expansion of spaces — in meaning, and as objects — harmonises visual material to a level plane. Here, bodies of research co-exist in a manner that questions the remit of research itself. The recurrence of familiar forms composes this reflexivity: both the work and Hamilton's original interests are situated under renewed scrutiny. Here, the works behave twofold: they are objects as receivers of ideas, while appearing to emit ideas themselves. Hamilton's work holds an internal logic based on the cultural connections of things: the implicit subtext of an idea, the lineage and physical sensibilities of images, or the curiosity and adaptability of an object's ontology. Tracing the shifting usages and sensitivities of an image, Hamilton brings the frequencies of authenticity and artifice into plain relief — their competing status collapsing. Multiple images or materials may extrapolate from one nucleus: a moth species, an Ed Ruscha gradient, a Robert Crumb figure, a Hamilton tartan swatch. The fundamental economy of Hamilton's choice however, allows the obvious to be both simple and complex; the permutations are high, though the "origin" is concentrated and transformational. Anthea Hamilton was born in London in 1978, where she lives and works. She was one of four shortlisted artists for the 2016 Turner Prize. Recent solo exhibitions include: The New Life, Secession, Vienna, Austria (2018); The Squash, Tate Britain, London (2018); Anthea Hamilton Reimagines Kettle's Yard, Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield, (2017); Lichen! Libido! Chastity!, SculptureCenter, Long Island City, New York (2015); Kabuki, The Tanks, Tate Modern, London (2012); Sorry I'm Late, Firstsite, Colchester (2012); Les Modules, Foundation Pierre Berge - Yves Saint Laurent, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France (2012). Her work has been presented as part of the British Art Show 8 and in numerous international venues including: the Schinkel Pavilion, Berlin (with Nicholas Byrne), the 13th Lyon Biennale, and the 10th Gwangju Biennale.

Image credits

Header image: David Salle (b. 1952) Autumn Rhythm, 2018 signed, titled, and dated "Autumn Rhythm" David Salle 2018 (on the reverse) oil and acrylic on linen 74 x 91 in. (188 x 231.1 cm.) © David Salle/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Skarstedt, New York